The journal Ethology has just published a study by the Natural Science Museum of Barcelona (MCNB) that sheds light on animals’ ability to recognise the dominance signals of other species when in a competitive scenario. Led by the Museum’s Vertebrates Curator, Javier Quesada, the study followed the behaviour of two related bird species that nest in holes and nest boxes and which inhabit Collserola Natural Park (Barcelona): the Blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus) and the Great tit (Parus major).

Parus major & Cyanistes caeruleus ( Martin Mecnarowski CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Animals use colours, morphological structures and behaviour to communicate their dominance and their ability to secure resources in adverse circumstances with individuals of the same (conspecific) species. For example, the Blue tit displays its dominance through the size of its natural black bib, which stands out in the centre of its intense yellow breast, a trait that is very well known among its congeners. The individuals with the thickest bibs are the most dominant. Yet, could the recognition of dominance cues also occur between different species? Theoretically, this might prove to be advantageous for the species interpreting the cue.

This study has set out to determine whether one species can identify the dominance signals of another, despite the difficulty involved in scientifically proving such ability.

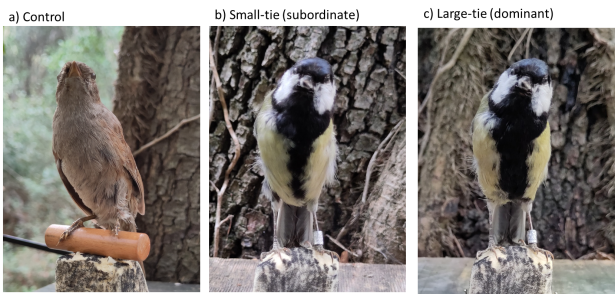

Model of a great tit (Parus major) placed on a nest box. Author: Javier Quesada/MCNB

In relationships of dominance between species, size is known to be a good indicator and predictor of the ability to obtain resources (the larger the species is, the more dominant it is). For example, the Great tit stands out as dominant over the Blue tit. The MCNB research team carried out several experiments simulating attempts to take over the nest box of the Blue tit when it was breeding. Different taxidermy models were placed on the top of the nesting box. One model represented a dunnock (Prunella modularis), an insectivore species that also inhabits the area used for the study and which in theory does not represent any sort of threat, as it does not breed in holes. The other two models resembled the Great tit, a dominant species that does compete with the Blue tit. In these cases, one model had a small bib and the other a large one.

Taxidermy models used in the study: A/ Dunnock (Prunella modularis) B/ Subordinate great tit (Parus major) C/ Dominant great tit (Parus major). Author: Javier Quesada/MCNB

The behaviour was monitored during the breeding seasons between 2014 and 2016, at the Can Catà Biological Study Area in Collserola Natural Park, where there are more than 230 nest boxes, primarily inhabited by these two tit species.

Results of the data analysis revealed that the Blue tits responded more aggressively to the Great tits than to the dunnock, which does not breed in holes. This showed that the Blue tits recognised the Great tit as a nest usurpation threat. It was also observed that Blue tits did not behave in the same fashion with the two different Great tit models (small or large bibs). The Blue tits took greater risks when they encountered a subordinate model (smaller bib) than when facing a more dominant and potentially more dangerous individual (larger bib). The study concludes that this small bird species is able to interpret the meaning of the black bib of the Great tit, therefore providing evidence of the existence of interspecific recognition of dominance through colour cues.

According to Javier Quesada, ” this research not only deepens our understanding of communication among different species, but also provides insight to the way they can very accurately interpret and distinguish the visual status cues of other species that might potentially have an impact on their survival and reproductive success”. He adds, “future studies will have to analyse and pinpoint the mechanisms behind this identification and explore whether these behaviours are genetically based or learned”.

Reference:

Quesada, J., Guallar, S., Navalpotro, H., Carrillo-Ortiz, J. G., & Senar, J. C. (2024). Recognizing interspecific dominance signals? Blue tits adjust nest defence based on great tit’s black bib size. Ethology, 13460. https://doi.org/10.1111/eth.13460